2024 World Chess Championship analysis: empirical synthesized approach | by Max | Dec, 2024

The 2024 World Chess Championship between Gukesh Dommaraju and Ding Liren captivated chess fans worldwide, culminating in an unforgettable finish where Gukesh claimed the title, becoming the youngest-ever World Chess Champion.

As a chess enthusiast, I followed the games closely — not in real time, as the lengthy durations conflicted with my daily responsibilities, but I made sure to watch full game overviews and analyze the overall dynamics and momentum. This allowed me to appreciate the nuances of the match and gain deeper insights into the strategies employed by both players.

In hindsight, it was an enjoyable match with plenty of action and momentum shifts, keeping me captivated throughout. It also sparked thoughts about player profiles, strategies, and game styles. When the match ended, I had mixed feelings about the outcome. On the one hand, Gukesh seemed a worthy and well-deserved titlist, but I couldn’t help but wonder: was this a fair result? What if Ding hadn’t blundered in that last game? What might have happened if the match had moved to tie-breaks, and how would that have shaped my impressions of the match overall? How did the players’ performances compare across the match as a whole? These reflections led me to analyze the match from an empirical and synthesized standpoint, aiming to form a cohesive picture of it as a whole. In this post, I will present my analysis process, share the results, and conclude with my final thoughts on the match.

From the early games of the match, Gukesh seemed to take control, adopting a more active and initiative-driven play style. Ding, by contrast, often appeared defensive, at times opting for early draws — even in games where he held the advantage with the white pieces. While this approach allowed Ding to stay in the match, it ultimately faltered in the final game. In attempting to simplify the position and force a draw, he turned an equal endgame into a decisive loss. This contrast in approaches not only defined the match’s narrative but also shaped its outcome, highlighting the risks and rewards of each player’s strategy.

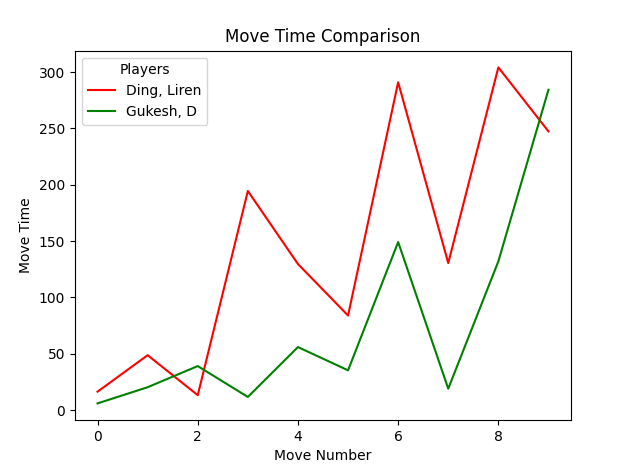

In addition, it became evident from both players’ time management that Gukesh appeared to be better prepared. He was typically faster during the opening phase and maintained a time advantage into the midgame, whereas Ding often found himself under time pressure. Ding spent significantly more time thinking, even in the opening moves, which may have contributed to his difficulties later in the match.

With all that said, I reminded myself that Ding only lost due to an unfortunate blunder in the last stages of the final game, while he was under time pressure. Had it not happened, the players would have continued to tiebreak games with faster time controls, where anything could have happened, and maybe Ding would’ve emerged as the winner in this scenario. Perhaps then Gukesh’s active and open style could be seen as careless and as a sign of inexperience next to Ding’s more conservative and balanced style. So perhaps my impression of the match was biased due to the final outcome?

Although many analyses of the match are available online, most tend to focus on a per-game breakdown, often neglecting cross-game synthesis and data-driven insights. I chose to adopt an empirical, holistic approach, which involves using raw game data as measurable evidence — data that is mostly easily accessible — and combining it to generate match-wide insights from a broader perspective. This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the match as a whole, rather than isolated evaluations of individual games.

During my analysis I decided to focus on several (mostly widely used) parameters, in an attempt to either support or refute the observations made earlier. List of the metrics used:

- Accuracy —A widely used metric on online chess platforms to evaluate how closely a player’s moves align with the optimal moves suggested by a chess engine. In this metric, engine-generated moves are considered ideal, and the player’s accuracy score is determined by measuring the degree of deviation from these optimal moves across the game.

Obtained from Lichess API. - Blunders, Mistakes, and Inaccuracies — Another widely used metric. It classifies errors based on three categories:

– Inaccuracy — mild deviation from optimal play, usually results in centipawn loss of 0–50

– Mistake — moderate deviation from optimal play, usually results in centipawn loss of 100–200.

– Blunder — severe deviation from optimal play, usually results in centipawn loss of >200.

Obtained from Lichess API. - Average Centipawn Loss (ACPL) — A commonly used chess metric to evaluate the quality of a player’s moves by measuring their deviations from the optimal moves suggested by a chess engine. In this context, a centipawn represents 1/100th of a pawn in material value. The lower the ACPL, the closer the player’s moves are to engine-recommended decisions, and thus, the better their play. Unlike the previos metric, ACPL offers a precise numerical value for performance, making it easier to directly compare players. It is particularly useful for highlighting consistency and minimizing errors over a game or match.

Obtained from Lichess API. - Move Times —This metric analyzes the time players take for their moves, segmented across games to identify preparation levels and time management trends, particularly in the opening phase. A significant clock advantage after the opening (we look at first ten moves) can indicate superior preparation and better time management skills. Additionally, this metric provides insight into players’ psychological states and game momentum, as faster moves often reflect confidence and familiarity with the position. For consistency, the segmentation aggregates all moves across games, regardless of piece color, combining a player’s first moves equally whether they play as White or Black.

- Conversion Rate — This metric tracks how effectively a player converts winning or advantageous positions into actual victories. Calculated by dividing the number of wins from advantageous positions by the total amount of advantageous positions throughout the match. I focused here on advantages of >100 centipawns. In case a player’s advantage drops below 100 centipawns it is counted as a lost advantage.

- Comeback Rate — This is the other side of the previous metric, meaning how effective is a player in surviving a disadvantage. Calculated by dividing the number of comebacks from disadvantageous positions by the total amount of disadvantageous positions throughout the match. I focused here on disadvantages of >100 centipawns. In case a player’s disadvantage drops below 100 centipawns it is counted as a comeback.

- Move Repetitions — This is perhaps the trickiest metric to define, as it lacks an official standard. The purpose of this metric is to quantify how often a player attempts to repeat a move immediately after it was played, typically aiming to achieve a draw through threefold repetition. This behavior can be seen as an unofficial draw offer. While there are cases where repeating moves is the best or only way to avoid worsening one’s position, such repetitions can reveal meaningful insights about the game. For example, it may highlight a player’s inclination toward passive play, focusing on securing a draw, rather than adopting a dynamic or risk-taking approach.

I downloaded the match PGNs from the official world championship website, complete with move times. As usual — raw data is dirty, so I had to automatically fill in some missing move times from the clock readings, and also one PGN was mistakenly uploaded instead of the correct one, so I reached out to the competition organizers to get this rectified. PGNs are also be available at chess.com, albeit without move times, just clock readings.

For the engine analysis data from Lichess (values such as accuracy, average centipawn loss, etc.) I had to manually upload each PGN to Lichess and request an engine analysis (unfortunately this functionality is not exposed via an API at the moment).

After that I could access these analyses via an API and iteratively process them to form a wholesome and cohesive view on the match.

Next we’ll go over the parameters we defined and discuss them one-by-one.

- Accuracy:

The accuracy appears to be almost equal and the difference between the players is negligible. Note this is average accuracy across all games, so although there could be a noticeable difference when you look at a one game or another, overall it seems both players played on a very similar and high chess level.

2. Blunders, Mistakes, and Inaccuracies:

The data on blunders, mistakes, and inaccuracies indicates that Ding played a more precise game, while Gukesh was more prone to errors. However, we must consider the severity of those errors. Ding made two blunders compared to Gukesh’s one, and, as we recall, it was that final blunder that cost Ding the match. This highlights the significant role error severity plays in chess match outcomes. It seems that while achieving 100% accuracy isn’t always essential, avoiding critical errors is absolutely vital. We can think of errors of varying severity as links in a chain, where the link strength is equally affected by the error severity and frequency. The more severe and frequent the error — the weaker the link. As the saying goes, “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.”

3. Average Centipawn Loss (ACPL):

The average centipawn loss shows a very slight advantage (less than 1 centipawn) for Ding. This is similar to the accuracy metric we got, which showed a negligible advantage for Gukesh.

4. Move Times:

The move times metric supported the earlier observations that Gukesh seemed more prepared and more confident throughout the openings. Ding spent visibly more time during the opening on each move and naturally this accumulates and results in rather large differences on the clock when the players enter midgame. It would be interesting to go deeper into this and maybe gain insights regarding how time pressure might have caused player’s mistakes or blunders.

5.6. Conversion and Comeback Rates:

Ding demonstrates a clear advantage in both the conversion and comeback metrics, outperforming his opponent in both aspects. It’s important to note that these metrics are inversely related: one player’s comeback rate impacts the other’s conversion rate, and vice versa. This suggests that Ding was not only more effective at capitalizing on his advantages but also displayed superior resilience, excelling in situations where survival and recovery were essential.

7. Repeated Moves:

Both players showed virtually the same amount of repeated moves. I expected Ding would have more repetitions as a reflection of his style, and in contrast to Gukesh’s seemingly more dynamic and open play. However, this assumption was not supported by this metric.

Performing an empirical, synthesized analysis of a chess match undoubtedly comes with challenges. Chess is inherently dynamic and versatile, where the outcome of individual games can differ drastically. For instance, a player might perform poorly in one game, committing multiple errors and losing, but then deliver a solid performance in the next game, capitalizing on a single error from their opponent to win. Despite an equal scoreline of 1–1, such swings in performance can skew overall evaluations, as cumulative mistakes from the first game may disproportionately affect perceived performance.

Another challenge lies in using engines as benchmarks for analysis. While engines provide valuable insights, their evaluation methods differ significantly from human reasoning. Engines often assess positions purely on objective grounds, overlooking critical human factors like time pressure, emotional strain, or practical playability. An engine might rate a position as equal because a player in an apparent disadvantage has drawing chances — provided they find a series of perfect moves. However, this fails to account for the immense difficulty of executing such precision in real-world scenarios.

Despite these limitations, empirical analyses can offer a complementary perspective alongside other methods, such as commentary from experienced players or chess bloggers, psychological evaluations of gameplay or behavioral patterns, and personal observations. By synthesizing these different angles, we can form a more nuanced understanding of the match.

In reflecting on this particular match, the data offered some surprising revelations that contrasted with my initial impressions. Objectively, Ding demonstrated slightly more precise and consistent play overall. Yet, his final critical blunder was decisive, costing him the title. Had the 14-game match ended in a draw, it might have been a fair outcome given Ding’s resilience and steadier performance. However, chess, much like professional sports, is unforgiving; one error can overturn everything. As the saying goes, “One mistake can undo a thousand good deeds.”

All the resources for this analysis, including the PGNs, the Lichess codes for the engine analyses, the python code used to analyze data and produce plots, and the full text of this post are open sourced in: https://github.com/maxamel/wcc2024

2024-12-18 09:15:44