How a Tale of Demonic Possession Predicted the Decline of an Early Medieval Empire

In the early ninth century, a Frankish courtier used stories of demonic possession to criticize the “many sins” of the kingdom’s leaders.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In the story, the devil calls himself Vigo.

as a frankish courtier Einhard According to reports, a young girl around 16 years old began erratic behavior Early ninth century AD Ultimately, the girl’s desperate parents have no choice but to seek an exorcism. They took her to a church in the kingdom Franksa country whose borders spanned much of Western Europe at the time. Some relics had recently been brought from Rome to consecrate the church, where the priest attempted to converse with the demon within the girl. Suddenly, there was a reply in Latin she didn’t understand. It was only then that Wiggo identified himself and frankly admitted what he had done.

Viggo claims that he is Satan’s gatekeeper. For the past few years, he has been roaming the lands of the Franks with 11 friends. “Follow our instructions,” the demon continued“We destroyed the grains, the grapes, and all the agricultural products of the earth that were useful to man. We slaughtered the livestock with diseases, and even transmitted pestilence and pestilence to men. The priest asked what gave Vigo such power. The demon answered : “Because of the perverseness of this nation, and the manifold sins of those who were appointed to rule over them. “

The sins of the Franks and their rulers made the land of Vigo and his friends fertile. It was a land where justice was devoid of justice and where greed was rampant: powerful men, Wigo said, “abuse their higher positions,” which “they gained in order to rule justly over their subjects, subjecting themselves to pride and vanity;” They harbor hatred and malice not only against those who are far away, but also against their neighbors and allied people. Friends do not trust friends, brothers hate brothers, and fathers do not love their sons. No one, Wiggo concluded, glorified God as much as previous generations. His speech ended, his work apparently accomplished, the demon left the girl, overcome by the power of the martyr’s relic.

Stories about the Middle Ages sacred or supernatural– Demons, Angels, Saints, Relics and Visions – The story takes place in a society where the lines between the natural and the supernatural are believed to have been blurred. thin or non-existent. They reflect widespread beliefs across social classes and, for modern historians, offer an opportunity to transcend tightly controlled elite circles. Descriptions of miracles, religious sermons, and other such cultural artifacts allowed medieval writers to conceal their critiques of power and reveal what real What’s going on in the world.

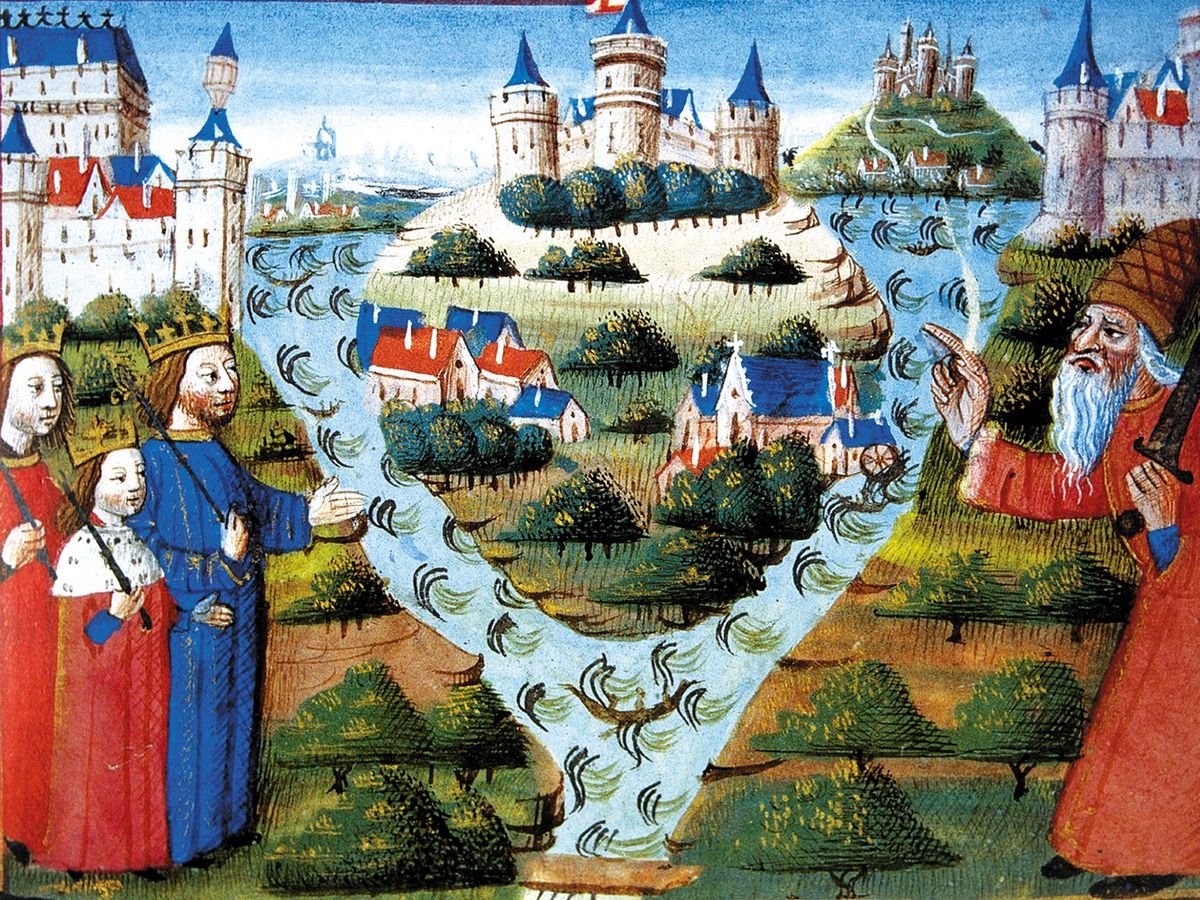

Map of the borders of the Carolingian Empire at its height in 814 AD (outlined in pink) and its subsequent division in 843 AD (outlined in orange, green and purple)

Vigo’s description of the kingdom is consistent with the situation in the kingdom at that time. its most famous leader, CharlemagneCame to power at the end of the eighth century as ruler of the Franks, a people known to the Romans since Late Antiquity, who had ruled their own independent kingdom since the end of the fifth century. After the coup of 751, members of the new Frankish dynasty—the Carolingians—expanded against their enemies at an alarming rate, establishing an empire that at its height stretched from the North Sea to the Pyrenees in the south and all the way to the Danube River . On Christmas Day, 800 AD, the Pope Charlemagne’s coronation As Roman Emperor in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Son and heir of Charlemagne, Louis the PiousIn 814, he succeeded his father as emperor.

but The unrest at the Frankish court in 829 culminated in an attempted coup in 830. march.

In a dictatorship like the Frankish Empire, direct criticism of the ruler was dangerous. It’s best to let Wiggo do it for you.

The specific story of demonic possession is preserved in a series miracle storyprobably written around 830 by a scholar named Einhardwho is best known for writing a famous Biography of Charlemagne. He was also a close associate of Louis the Pious and was so respected at court that he served as childhood tutor to Louis’ eldest son, the future emperor. Lothar I.

Illustration of Einhard as scribe

Einhard was not happy with the status quo, but criticizing the emperor to his face was traditionally a bad career move for a courtier. Instead, Einhard used a local story about a young girl possessed by a demon to anchor his critique, likely drawing on wider popular perceptions of the recent unrest.

Einhard ends his account of Vigo’s possession by breaking from the narrative, writing in his own voice as a courtier: “Ah, what a pity! What a misery our time has fallen into, with evil devils instead of good men. Becoming a teacher, a supporter of evil and an instigator of crime, we are warned to correct ourselves. Witnessing the actions of men and women who opened the mouth of hell, Einhard wrote to Louis with a warning in Political Consensus. Always fragile under the projection of power that has now begun to fray, the position of the ruler and queen remains fragile. In other words, Einhard is saying that until the ship of state returns to normal, those plotting a coup against the political order. Will almost always try again.

Our new book, Oathbreakers: The fraternal war that shattered empires and created medieval Europetells the gripping and often horrifically violent story of the collapse of Charlemagne’s empire. To justify their rule, the Carolingians told a story about themselves as God’s chosen people, which was inevitable and more or less infallible. In fact, they were a mess. Their rule began with a coup, and they never really stopped plotting. Although the royal family claims to be stable administrators, they like to try to overthrow current rulers. Charlemagne’s eldest son Pepin the Hunchback launched a coup against Charlemagne in 792, but failed. Then, a few years after Louis took control of the empire in 814, he heard the wind claiming that his nephew might be plotting a coup, and responded by blinding himself, killing the alleged plotter. Louis faces two more serious problems coup attempt In the 830s.

Epitome of medieval Louis the Pious expelling his son Pepin I of Aquitaine

The coup attempt in 830 that prompted Einhard to immortalize Vigo’s folk memory was dramatic, revealing the deep divisions behind the veneer of elite comity and consensus. On one occasion, the rebels (including the emperor’s second son, Pepin I of Aquitaine)capture Judith of Bavaria—Louis’ second wife, resented by the children of his first marriage — dragged her from shelter In the cathedral, torture would have been possible for her, and of course her life would have been threatened. They forced her to confess to witchcraft and adultery. The conspirators also arrested several rivals in court and executed them. For a moment, the coup seemed successful.

But eventually Louis’ eldest surviving son, Lothar, stepped in and brokered a deal that restored the status quo. Lothar arrived with a small army to succeed Pepin I, announcing that the fate of their father and the queen would be decided in a few months at a gathering in the far east. This brilliant move diverted operations away from the areas where the insurgents had the most support and allowed tempers to cool. In fact, at that conference in Nijmegen (now the Netherlands), the assembled magnates and their armies decided that things had gone too far and restored Louis to the throne.

Historians can look back at the tensions leading up to the coup of 830 and how its lack of resolution led to another coup attempt in 833 and ultimately to a coup. brutal civil war In the 840s. But for all the murders, treasons, and conspiracies, most of the historical information comes from fulda yearbook arrive annual book of saint bertinremains committed to the myth of stability, inevitability, and God’s blessing. this annual book of saint bertinFor example, suggesting that the empire returned to normal after the coup belies just how tumultuous those years really were. At the end of entry 830, the text state“Your Majesty the Emperor [Louis] regained control of the situation. He ordered the detention of those responsible for what had happened to him, whose duplicity had been discovered, and whose plots had been exposed, until another conference could be held in Aachen.

Illustration of the Battle of Fontenoy, a decisive conflict between Charlemagne’s three grandsons in 841

In other words, the historian says that things returned to their “natural” state and the emperor returned to power. The ship always seems to simply right itself, returning to what the elites pretend is the natural order of things.

What’s more, these sources tended to report the views of the most powerful, concealing dissent and certainly not paying attention to the attitudes of civilians, as second-hand versions such as Wigo’s story reveal. The victors don’t always write history, but courtiers do sometimes need to keep criticism low. Still, the stakes were too high for Einhard to remain silent. Therefore, he wrote indirectly, using a demon named Vigo to express the concerns of the entire Frankish people.

Perhaps more importantly, the stories of Wigo and similar figures are how they reveal how observers, from courtiers to peasant girls, viewed high politics and elite greed. The chaos of the Carolingian Empire led to the collapse of the ruling dynasty, pitted nephews against their uncles on the battlefield, and created countless grieving mothers. But as Einhard makes clear, the rampant greed of the kingdom’s ruling class led to widespread misery—famine, pestilence, and pestilence, a feeling that the gates of hell had been opened, and, in Einhard’s words, Forcing peasant families and their little girls to bear the heavy burden of all the sins of their rulers.

Adapted from Oathbreakers: The fraternal war that shattered empires and created medieval Europe go through Matthew Gabriel and David M. Perry. Published by Harper. Copyright © 2024.

Note to readers

Smithsonian Magazines participates in an affiliate link advertising program. If you purchase something through these links, we may receive a commission.

2024-12-10 17:23:35