As a NASA spacecraft made a historic close flyby of the sun just before Christmas, scientists on Earth had one question on their minds: Did their probe survive as an epic Christmas gift? Or a burnt piece of coal in space?

They won’t know for a few days at all, at least until NASA’s spacecraft Parker Solar Probe — called home on Friday (December 27) with a simple “status beacon” to let its science team know everything was OK. But the scientists behind On December 24, the spacecraft flew past the sun There is confidence that their spacecraft will survive the trip.

“Today, the Parker Solar Probe has achieved the mission goals we designed,” said Nicola Fox, NASA’s associate administrator for science missions. said in video update Tuesday. “Currently, Parker Solar Probe is closer to the star than ever before, and that’s the orbit we really designed the mission to be on.”

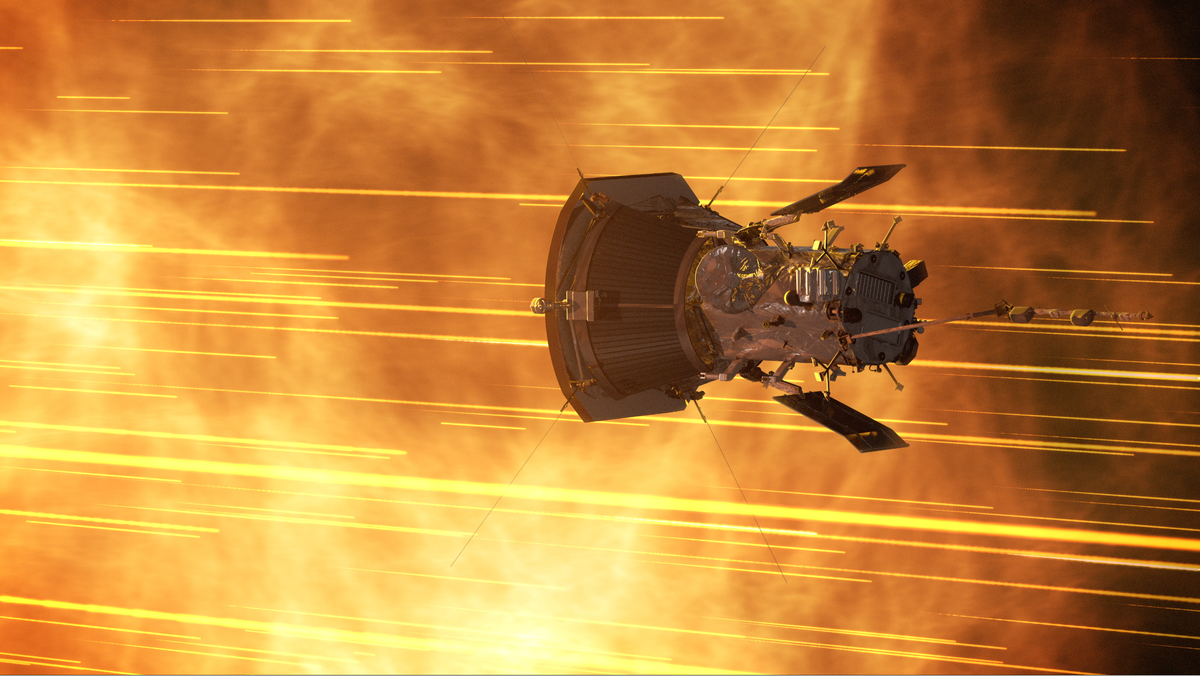

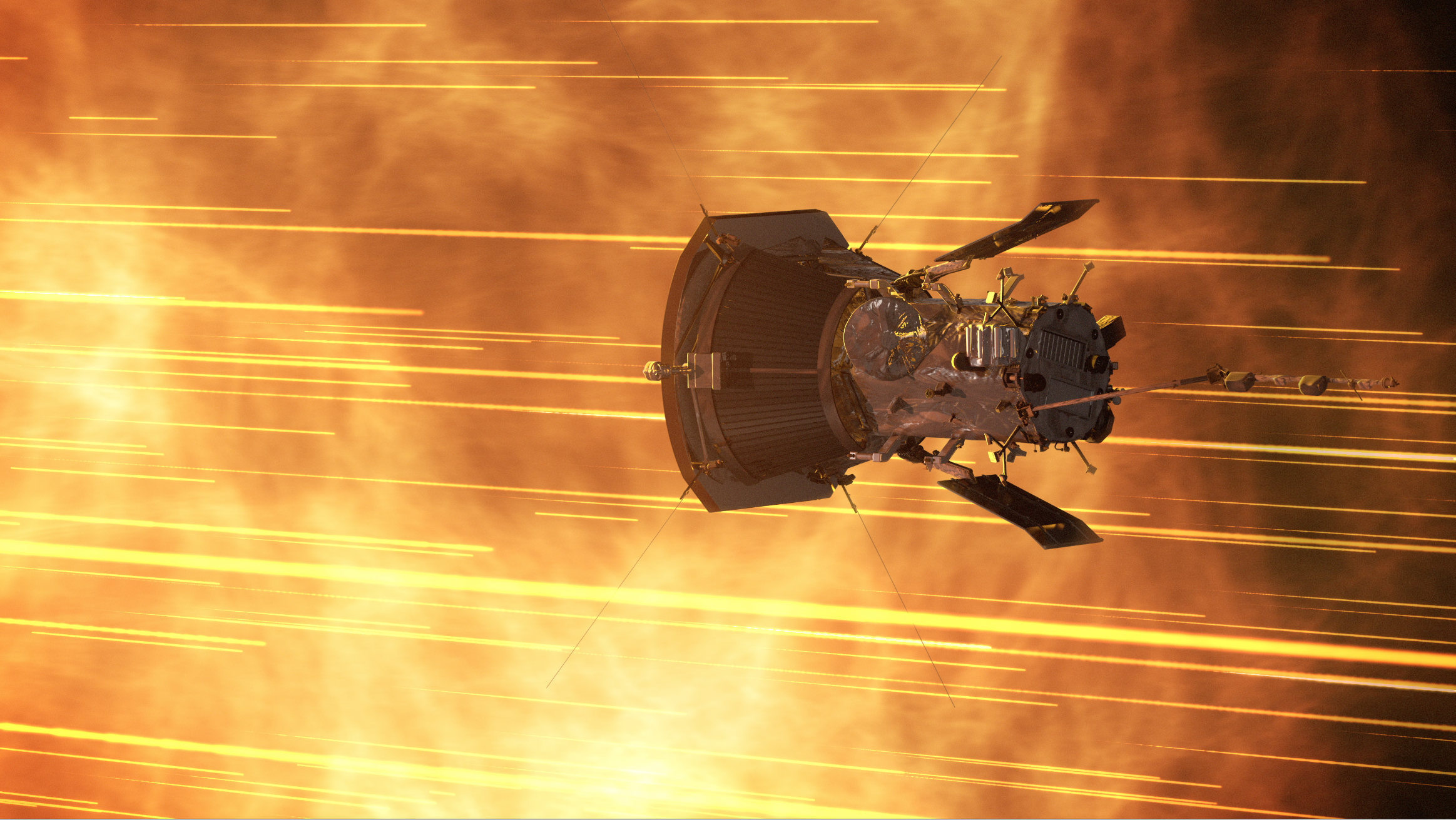

The Parker Solar Probe flew within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface and “contacted it.” sun” Tuesday, closest distance to a star by any man-made object. NASA said the spacecraft passed the sun at an astonishing speed of 430,000 miles per hour (690,000 kilometers per hour), making it the fastest spacecraft ever built. It is expected to experience scorching temperatures of up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (980 degrees Celsius) during this encounter.

But the entire flyby process is automated. Scientists last heard from Parker Solar Probe it’s friday night (December 20), NASA officials stated in the latest news at the time that the beacon transmission from the probe “indicates that all spacecraft systems are operating normally.”

Scientists at the Mission Operations Center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, won’t receive the next call from the spacecraft until around midnight on Friday, Dec. 27.

JHUAPL spokesman Michael Buckley told Space.com in an email: “We expect Parker to send out the first signal after closest approach (like on December 20), which is a signal indicating only the general health of the spacecraft. beacon); the signal is expected to be emitted around midnight. JHUAPL is overseeing NASA’s $1.5 billion Parker Solar Probe mission.

Parker Solar Probe is expected to issue a more reliable status update on New Year’s Day, January 1, when the spacecraft will beam telemetry and housekeeping data to Earth for the first time since its flyby. Only then, Buckley said, will scientists know whether the spacecraft collected the expected solar observations from the flyby.

“This allows the team to better understand the overall health of the spacecraft and subsystems/instruments, including whether Parker’s data recorder is full,” he wrote.

The Parker Solar Probe’s close flyby of the sun on Christmas Eve was the pinnacle of the spacecraft’s mission. NASA launched the probe in 2018 Its mission is to study the Sun like never before, but to do so the spacecraft must get closer to the star than anything ever built by human hands in history. Scientists hope the detector will help explain why the outer sun’s atmosphereLike its corona, it is much hotter than the surface of the star itself.

To get closer to the sun, the Parker Solar Probe flew by Venus seven times to stop gravity from accelerating it to its current speed. It also orbits the sun 21 times, accelerating and getting closer each time it passes. The Dec. 24 flyby marked the Parker Solar Probe’s 22nd flyby of the sun and the closest the probe has ever come to a star. NASA says it has at least two more orbits traveling at the same speed and distance from the sun.

“This is an example of a bold NASA mission that does something no one else has ever done to answer long-term questions about our universe,” Arik Posner, Parker Solar Probe project scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said Dec. 20 said in a statement. “We can’t wait to receive the first status updates from the spacecraft and start receiving science data in the coming weeks.”

If all goes well, the first science data from the Parker Solar Probe’s Christmas Eve flyby of the sun should be transmitted to Earth in late January, mission officials said.